Teaching Philosophy

My greatest wish is that my students leave the classroom feeling inspired by and talking about the material. Students discussing material outside of the classroom are students who have engaged with the material on a deeper level. They are demonstrating both their interest in learning and a personal connection to the subject matter. To facilitate students’ continued interest in my courses after class ends, I make a concerted effort to teach with enthusiasm for the material, I present material in a way that is accessible to students of all skill levels, and provide life-relevant examples, activities, and demonstrations to help them connect the material to their own lives.

Enthusiasm is contagious.

To me, teaching is not just about sharing knowledge, it is about sharing excitement. My teaching reflects my enthusiasm for the subject matter I’m presenting. Every class period, I engage my students with a smile. I refuse to seem bored or exasperated with my own lecture topics! I am also not afraid to share when I think something is particularly cool. For example, when we reach my personal favorite topic of vision in Introductory Psychology or Sensation and Perception courses, I always begin the first lecture on that topic by turning out all the lights, opening the window curtains, and saying, “All the light that we’re seeing right now has traveled 93 million miles from the sun, bounced off all of the surfaces in this room, just to end its epic journey in your eyeballs. Your eyes and visual system have evolved over 3.5 billion years to not only detect light, but to allow you to experience light: your brain interprets the light information detected by your eyes to give you the rich visual experience you are so accustomed to. How cool is it that you can see?”

I continually find evidence that enthusiasm is contagious. My students actively participate in lectures and discussions, they offer their own anecdotes and prior knowledge, make connections and wonder aloud about how the material is related to their lives. I also receive feedback from students every semester saying that I made boring topics interesting, that they did not expect to like the course due to the subject matter, but ended up enjoying it anyway, that they hated Psychology in high school, but loved my class. The feedback I receive at the end of the semester and my students’ willingness to participate in class indicates that my enthusiasm inspires them to engage with the material in a way they would not have otherwise.

Enthusiasm is contagious.

To me, teaching is not just about sharing knowledge, it is about sharing excitement. My teaching reflects my enthusiasm for the subject matter I’m presenting. Every class period, I engage my students with a smile. I refuse to seem bored or exasperated with my own lecture topics! I am also not afraid to share when I think something is particularly cool. For example, when we reach my personal favorite topic of vision in Introductory Psychology or Sensation and Perception courses, I always begin the first lecture on that topic by turning out all the lights, opening the window curtains, and saying, “All the light that we’re seeing right now has traveled 93 million miles from the sun, bounced off all of the surfaces in this room, just to end its epic journey in your eyeballs. Your eyes and visual system have evolved over 3.5 billion years to not only detect light, but to allow you to experience light: your brain interprets the light information detected by your eyes to give you the rich visual experience you are so accustomed to. How cool is it that you can see?”

I continually find evidence that enthusiasm is contagious. My students actively participate in lectures and discussions, they offer their own anecdotes and prior knowledge, make connections and wonder aloud about how the material is related to their lives. I also receive feedback from students every semester saying that I made boring topics interesting, that they did not expect to like the course due to the subject matter, but ended up enjoying it anyway, that they hated Psychology in high school, but loved my class. The feedback I receive at the end of the semester and my students’ willingness to participate in class indicates that my enthusiasm inspires them to engage with the material in a way they would not have otherwise.

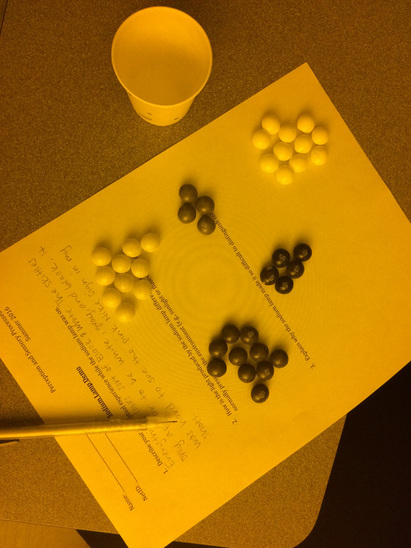

Skittles under a sodium lamp--colors clockwise from the top left: orange, red, yellow, purple, green.

Skittles under a sodium lamp--colors clockwise from the top left: orange, red, yellow, purple, green.

Clarity and approachability are key.

Enthusiasm can only carry a student so far, however. The clarity and approachability of the lesson is also critical to their success and their ability to connect to the material. My introductory Psychology classrooms are full of students with varying skill levels and background knowledge about the subject—some are taking their very first Psychology class, while others may have taken one or more Psychology classes in high school. Similarly, my 200-level Sensation and Perception students vary in their comfort-level with the more “science-intensive” side of Psychology, as they like to put it. No matter the setting, it is my job as instructor to bring everyone onto the same page and to make the material approachable for all so that my students have a solid knowledge base to continue on in the field if they so choose, or to find ways to apply the material to their lives if their course of study leads them elsewhere. Towards this end, my lessons are thorough and have a logical flow. During lectures, I regularly ask probing questions to check my students’ understanding and return to topics they seem unsure about. I make sure all activities, discussions, or assigned homework have a clear purpose and relationship to the material.

Many of these activities, discussions, and homework assignments not only serve as a review of material, but also give students the opportunity to experience the concepts first hand. A popular demonstration I’ve used in both introductory classes and Sensation and Perception involves the use of a sodium lamp. When students are learning about color perception, an important concept they must remember is the importance of the light source. When we are under normal lighting, like sunlight or fluorescent light, we can see all the colors of the rainbow. However, if we are under a light source that emits only a few wavelengths of light, such as a sodium lamp (think, old fashioned yellow street lights), color perception becomes very difficult. Instead of a rainbow of all of the colors, we see only shades of the color of the light source—yellow in this case. In class, my students attempt to sort colored candies under a sodium lamp to memorably demonstrate that color really is just a product of what light is available for our visual system. Demos such as this one serve to make the material more approachable to students and provides them a memorable anchor for their knowledge within my course and after they leave.

Connect to life outside the classroom.

Finally, while it is important to me that students are inspired by my classes and that they learn the subject matter at hand, it is perhaps most important that they find ways to apply their new knowledge to their lives. I encourage my students to think critically and scientifically about things they learn in my class and future classes, about psychological claims they see in the media and about decisions they make in their lives more broadly. As a psychology instructor, I am in the unique position of conferring subject knowledge that directly contributes to my students’ understanding of themselves and I take that role seriously. Throughout my lectures, I offer my students examples of how they can relate the material to their own experiences. For example, every semester, my developmental psychology lesson in my Introductory Psychology courses falls conveniently around a break. So, every semester I ask my students to either explain a few developmental principles to their parents and ask for some stories about their childhood that fit into those principles or to test out some developmental concepts on their younger relatives. They then write up a short report explaining the evidence they found for developmental psychology in their own lives. In general, I often find my students will take the job of relating the material to their own lives upon themselves—offering me examples of how they think the material relates to their lives in class or via emails to me outside of class. This form of student participation is more diagnostic to me than test scores because it indicates they are experiencing the material on a deeper level.

The confidence and enthusiasm my students demonstrate in their knowledge by participating in class and by relating the material to their lives gives me hope that they leave class thinking and talking about the material. And, if that is the case, I trust that they will continue to think and talk about the material in the coming weeks and years, continuing to apply the knowledge we shared to improve their lives in the long term.

Enthusiasm can only carry a student so far, however. The clarity and approachability of the lesson is also critical to their success and their ability to connect to the material. My introductory Psychology classrooms are full of students with varying skill levels and background knowledge about the subject—some are taking their very first Psychology class, while others may have taken one or more Psychology classes in high school. Similarly, my 200-level Sensation and Perception students vary in their comfort-level with the more “science-intensive” side of Psychology, as they like to put it. No matter the setting, it is my job as instructor to bring everyone onto the same page and to make the material approachable for all so that my students have a solid knowledge base to continue on in the field if they so choose, or to find ways to apply the material to their lives if their course of study leads them elsewhere. Towards this end, my lessons are thorough and have a logical flow. During lectures, I regularly ask probing questions to check my students’ understanding and return to topics they seem unsure about. I make sure all activities, discussions, or assigned homework have a clear purpose and relationship to the material.

Many of these activities, discussions, and homework assignments not only serve as a review of material, but also give students the opportunity to experience the concepts first hand. A popular demonstration I’ve used in both introductory classes and Sensation and Perception involves the use of a sodium lamp. When students are learning about color perception, an important concept they must remember is the importance of the light source. When we are under normal lighting, like sunlight or fluorescent light, we can see all the colors of the rainbow. However, if we are under a light source that emits only a few wavelengths of light, such as a sodium lamp (think, old fashioned yellow street lights), color perception becomes very difficult. Instead of a rainbow of all of the colors, we see only shades of the color of the light source—yellow in this case. In class, my students attempt to sort colored candies under a sodium lamp to memorably demonstrate that color really is just a product of what light is available for our visual system. Demos such as this one serve to make the material more approachable to students and provides them a memorable anchor for their knowledge within my course and after they leave.

Connect to life outside the classroom.

Finally, while it is important to me that students are inspired by my classes and that they learn the subject matter at hand, it is perhaps most important that they find ways to apply their new knowledge to their lives. I encourage my students to think critically and scientifically about things they learn in my class and future classes, about psychological claims they see in the media and about decisions they make in their lives more broadly. As a psychology instructor, I am in the unique position of conferring subject knowledge that directly contributes to my students’ understanding of themselves and I take that role seriously. Throughout my lectures, I offer my students examples of how they can relate the material to their own experiences. For example, every semester, my developmental psychology lesson in my Introductory Psychology courses falls conveniently around a break. So, every semester I ask my students to either explain a few developmental principles to their parents and ask for some stories about their childhood that fit into those principles or to test out some developmental concepts on their younger relatives. They then write up a short report explaining the evidence they found for developmental psychology in their own lives. In general, I often find my students will take the job of relating the material to their own lives upon themselves—offering me examples of how they think the material relates to their lives in class or via emails to me outside of class. This form of student participation is more diagnostic to me than test scores because it indicates they are experiencing the material on a deeper level.

The confidence and enthusiasm my students demonstrate in their knowledge by participating in class and by relating the material to their lives gives me hope that they leave class thinking and talking about the material. And, if that is the case, I trust that they will continue to think and talk about the material in the coming weeks and years, continuing to apply the knowledge we shared to improve their lives in the long term.